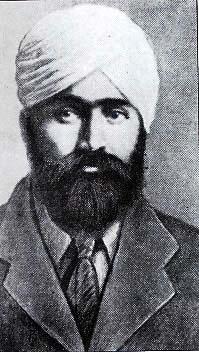

Canada's forgotten martyr Mewa Singh

By Jagdeesh Mann (@Jagdeesh Mann),

Special to The Post

Depending on whom you ask, the actions of Louis Riel, and Dr. Norman Bethune, along with others who lived through difficult times, can be seen as verging on treasonous or justified. Add to that list Mewa Singh.

Outside of Canada’s sizeable two million plus South Asian community, few Canadians will have heard of Singh who is revered as a Che Gueverra-like figure, in particular by Sikhs. A new play, The Undocumented Trial of William C. Hopkinson, opening at the Vancouver Art Gallery on Friday, January 8th is the first major artistic production to re-evaluate a man whom many view as Canada’s forgotten martyr.

In the play, Mewa Singh is placed on the stand to answer for his real life shooting and killing of William Hopkinson, a Canadian immigration official. The incident took place in the same art gallery one hundred and one years ago on October 21, 1914 when it served as the Vancouver’s Provincial Courthouse.

On that morning, Singh walked up to the third floor rotunda and killed Hopkinson with four shots from his revolver. He then handed over his weapon to the authorities and took full responsibility for his act, knowing he would receive capital punishment.

“I shoot. I go to station,” he proclaimed, in his limited English.

Within three months on January 11, 1915, Singh was hung from the gallows in New Westminster. He died at age 33, the same age as Hopkinson.

Despite the violent nature of Singh’s act, he has been lionised by Canada’s Sikh community in the same way Louis Riel has been by the country’s Metis population. Though he is a character written into Canadian history books as an assassin, in the Sikh community he is their version of Tiananmen’s Tank Man, the solitary protestor saying no and standing his ground against the machinery of institutionalised repression.

There are numerous sports and literary events organised annually in his tribute. The dining hall in Vancouver’s Ross Street Sikh temple, the country’s largest gurudwara where India’s Prime Minister Modi stopped by with Stephen Harper for a visit last April, bears his name and iconic image in memorial.

For playwright Paneet Singh, The Undocumented Trial of William C. Hopkinson, is a forum to cast light on the murky events that led to the shooting and to reveal the social conditions that made the collision between Singh and Hopkinson unavoidable.

“I have been surrounded by this story since I was a child, when my mother would tell it to me,” said Singh. “Mewa Singh’s name resonates in the South Asian community but it has been locked out of the mainstream. This play exposes his actions through the framework of the times in which he lived in order to move the story in to the 21st century. He stood up in the most difficult of circumstances and follows in the tradition of other Canadian martyrs like Louis Riel.”

Hopkinson and Singh were born and raised in India, and in adulthood, both migrated to Vancouver. Singh left a small village near Amritsar, Punjab to find his fortunes while Hopkinson left his post as a policeman after his first wife died. The Raj in India was beginning its slow fade. Hopkinson had never lived in England and so chose to renew his life in Vancouver.

But at the turn of the 20th century, Canada’s promise as a new world Gold Mountain came with caveats for non-white immigrants over their European counterparts. The Canadian government had institutionalised racism through legislation like the Chinese Head Tax and the continuous journey clause. The latter was utilised in 1914 in the infamous the Komagata Maru incident which was playing out at the same time as the Singh versus Hopkinson duel.

Despite holding very different stations in life, the destinies of Hopkinson and Singh became intimately tied to each other in BC. Hopkinson’s fluency in Hindi landed him a job as a government agent. His assignment was to harvest information from the Sikh community about their sympathies for Indian independence from British rule. He had a number of active moles in the community burrowing for intelligence.

Hopkinson’s methods were as heavy handed as his agents were clumsy – they shot and killed two Sikhs at the local temple. Hopkinson threatened Mewa Singh to become an informant, or to find himself the next target.

What Hopkinson didn’t anticipate, was that Singh would accept death before turning. Killing Hopkinson would not save Singh, it would only give rise to another Hopkinson. But making a public statement by killing him in the open and by embracing the death penalty would make a statement that resonates to this day.

For Sikhs in Canada who were struggling for a foothold in Canada at the time, Singh’s defiance would inspire their push for political equality – an achievement coming thirty years later in 1947 when South Asians and Chinese were granted the right to vote. Mewa Singh’s singular act echoes still in the disproportionate success of South Asians in Canadian politics – there are 16 MP’s of Sikh heritage currently serving in Canada’s Parliament. Had the Chinese community their own version of Mewa Singh, perhaps they too would be better represented at the highest politics levels.

William Hopkinson’s pernicious agenda was a spear foiled by Mewa Singh’s shield. Hopkinson left India seemingly to find his piece of the Cotswolds in the new world. But the new world would not be shaped by the old rules, as he fatefully discovered in his encounter with Mewa Singh.

Neither could have foreseen the modern multicultural Canada their clash would inadvertently help cast.

For more information on the play click on the link for The Undocumented Trial of William C. Hopkinson.

This piece was published in The Globe & Mail.